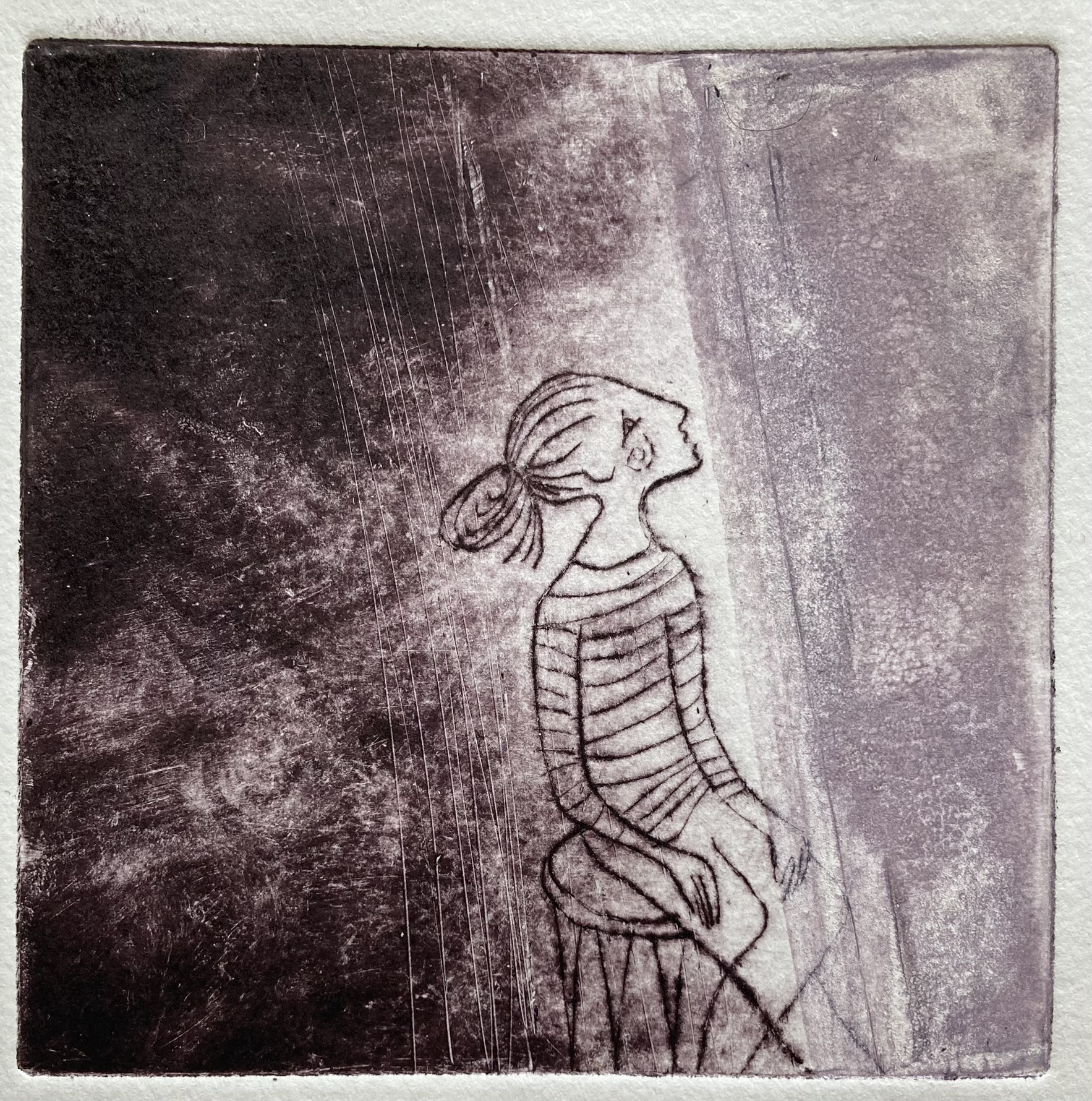

Approaching Mystery

Approaching Mystery

"Najpiękniejszym doświadczeniem, jakie może stać się naszym

udziałem, jest tajemnica.

Jest ona źródłem wszelkiej

prawdziwej sztuki i nauki.''

Albert Einstein

Do dzisiejszego postu zainspirowały mnie eseje Rebecci Stott, angielskiej pisarki, z cyklu Beautiful Strangeness, prezentowane w pięciu podcastach BBC Sounds. (Jednym z moich ulubionych miejsc.)

Opowiadają one o tym, że w naszym życiu — już od dzieciństwa — towarzyszą nam chwile i wydarzenia dziwne, tajemnicze, takie, na których opisanie brakuje nam języka. Chwile, których nie rozumiemy, a które pozostawiają nas w niemym zdumieniu.

Juz wyobraźnia dziecka zdaje się mieć dostęp do jakiegoś tajemniczego miejsca, z którego czerpie, próbując tłumaczyć sobie jeszcze niezrozumiały świat — miejsca pełnego głosów, stworów i postaci, które raczej zachwycają, niż przerażają. Ten świat z czasem oczywiście blednie, ale — jak przekonuje Stott — nasze dalsze losy wciąż tkane są z delikatnych nici realizmu i magii.

Tej magii najpełniej doświadczają ludzie ciekawi — poszukiwacze: naukowcy i artyści. To oni swoje idee i pomysły czerpia z miejsc jeszcze nie odkrytych, porównowalnych do "ciemnego strychu", gdzie intuicyjnie odgadują kształty swoich wizji, zanim zobaczą je ukończone i w pełnym świetle.

Pisarka opowiada, że artystom, w akcie twórczym zdaje się towarzyszyć jakaś obecność. Obecność, która prowadzi, szepcze, podpowiada choćby kolejne frazy. Wystarczy, że zaczną słuchać ''at the end of there nerves, at the limit of their capicity'' — a otwiera się przed nimi tajemniczy, inspirujący świat na granicy snu i jawy, z którego mogą czerpać.

Stott dodaje, że ta obecność jest czymś większym niż sam artysta — czymś bardziej otwartym i bardziej glębokim.

Chwile na granicy realizmu i magii pojawiają się jednak nie tylko w czasie tworzenia. Doświadczamy ich także w momentach ostatecznych — na przykład wtedy, gdy towarzyszymy najbliższym w ich umieraniu. Stott opisuje znak nadchodzącej śmierci, który pojawił się nagle gdy umierał jej ojciec: nadlatującą białą sowę w zimowym krajobrazie. To ona uświadomiła pisarce, że to już — że nadeszła chwila odejścia jej ojca. Sowa towarzyszyła tej śmierci i odleciała, gdy wszystko się dokonało. Wydarzyło się coś niezwykłego i magicznego — czego Stott nie próbuje wyjaśniać, tylko przyjmuje to z wdzięcznością.

W kontekscie odchodzenia i żałoby pisarka przywołuje takze Joan Didion i jej koncepcję "magicznego myślenia" — gdy mysli sie zupelnie innymi kategoriami, żeby przetrwac strate oraz zauważa niezwykłe wyostrzenie w tym czasie naszych zmysłów i podświadomości, które wyczula nas na najdrobniejsze anomalie. Ten stan często skutkuje zjawiskami takimi jak żałobne halucynacje: gdy wydaje nam się, że na ulicy widzimy osobę, która już odeszła.

Stott mowi, że tego magicznego myślenia wobec tajemnicy śmierci bardzo potrzebujemy. Potrzebujemy rytuałów — zasłaniania luster, zapalania świec. Pomagają nam one w jakiś sposób przejść przez proces odchodzenia najbliższych i odnaleźć się w świecie, który na chwilę traci swoje kontury.

Podsumowując, stajemy w obliczu nieznanego w chwilach wzmożonego uniesienia: gdy marzymy, gdy tworzymy i gdy odkrywamy kolejne tajemnice natury i wszechświata. Tajemnica towarzyszy nam także przy narodzinach i śmierci. Nie powinniśmy się tego ani bać, ani temu zaprzeczać. Stott przypomina słowa Einsteina, który twierdził, że tajemnica jest jednym z najpiękniejszych doświadczeń — że prowadzi do zachwytu, bez którego człowiek traci jakąś część swojego człowieczeństwa.

Swoje eseje Stott kończy słowami, które bardzo we mnie rezonują. Mówi:

"Doszłam do momentu, w którym przyjmuję magiczne myślenie. Dlaczego czuję się z nim bardziej komfortowo niż wcześniej? Ponieważ mam więcej respektu dla tajemnicy umysłu i dla dziwnych rzeczy, które czasami przydarzają się nam, gdy zatapiamy się w wyobraźni, gdy tworzymy czy przechodzimy żałobę. Mam więcej respektu dla ''beautiful strangeness'', która wydaje się być częścią tajemnicy naszej świadomości. (…) Odnajduję się w tym, co migotliwe, nieostre, cieniste i niepewne. Czuję się z tym komfortowo i celebruję te chwile. Nie — ja wręcz pielęgnuję tę przepiękną niezwykłość istnienia".

Ale pięknie.

Pozostaje mi polecić eseje Rebbecki Stott, kto ma mozliwosc odsluchania. Sa niezwykle inspirujace i skałniają do refleksji.

To z milością,

K

I niezmiennie zapraszam tam ---->

fb: @between.words.2025

in: @kasia_m.baranowska

Approaching Mystery

"The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious.

It is the source of all true art and science."

Albert Einstein

Today's post was inspired by Rebecca Stott's essays from the series Beautiful Strangeness, presented in the BBC Sounds — one of my favourite places.

They speak of the fact that, in our lives — from early childhood onwards — we are accompanied by moments and events that are strange and mysterious, moments for which we lack language. Moments we do not understand, and which leave us in a kind of wordless astonishment.

Even a child's imagination seems to have access to some secret place from which it draws, attempting to make sense of a world not yet fully understood — a place filled with voices, creatures, and figures that enchant rather than terrify. This world, of course, fades with time, but — as Stott suggests — our later lives are still woven from delicate threads of realism and magic.

It is this magic that curious people — seekers — experience most fully: scientists and artists. They draw their ideas and intuitions from places not yet discovered, comparable to a "dark attic," where they intuit the shapes of their visions before they see them finished and brought fully into the light.

To these scientists, and to artists as well, there seems to accompany the creative act a certain presence — a presence that guides, whispers, suggests even the next phrase. It is enough that they begin to listen "at the end of their nerves, at the limit of their capacity," and a mysterious, inspiring world opens before them — one that lies on the threshold between sleep and waking, and from which they may draw.

Stott adds that this presence is something larger than the artist alone — something more open, and deeper.

Moments at the boundary between realism and magic appear not only in acts of creation. We experience them also in final moments — for instance, when we accompany those closest to us in their dying. Stott describes a sign of approaching death that appeared suddenly as her father was dying: an barn owl flying in across a winter landscape. It was this owl that made her realise that the moment had come — that her father was about to depart. The owl accompanied the death and flew away when all was done. Something extraordinary and magical occurred — something Stott does not attempt to explain, but instead receives with gratitude.

In the context of dying and grief, Stott also invokes Joan Didion and her notion of "magical thinking" — a way of thinking in entirely different categories in order to survive loss — as well as the remarkable sharpening of our subconscious during such times, which sensitises us to the smallest anomalies. This state often gives rise to phenomena such as grief hallucinations, when we think we glimpse in the street someone who has already gone.

Stott says that we deeply need this magical thinking in the face of the mystery of death. We need rituals — covering mirrors, lighting candles. In some way, they help us move through the process of losing those we love and find our bearings again in a world that, for a moment, loses its contours.

In conclusion, we stand before the unknown in moments of heightened intensity: when we dream, when we create, and when we uncover further mysteries of nature and the universe. We approach mystery at birth and at death. We should neither fear this nor deny it. Stott recalls Einstein's words, in which he claimed that mystery is one of the most beautiful experiences — that it leads to wonder, without which a human being loses some essential part of their humanity.

Stott ends her essays with words that resonate deeply with me. She says:

"I have become more comfortable with that magical thinking. Why do I feel more comfortable? Because I have more respect for the mystery of the mind, and for the uncanny things that we sometimes experience as we dream, or create or grieve. I have more respect for 'beautiful strangeness,' which seems to be part of this mysterious thing we call consciousness. (…) I have come at home in the flickering, the indistinct, the shadowy, the uncertain. They are not just comfortable either; I celebrate — no — I cherish the beautiful strangeness of things."

How beautiful.

All that remains is for me to recommend Rebecca Stott's essays to anyone who has the opportunity to listen to them. They are deeply inspiring and invite reflection.

With love,

K

You will find me there too ---->

fb: @between.words.2025

in: @kasia_m.baranowska

And I will play the record ''Canes of Karabath'' by kIRk.

Stay tuned.

K.