In the blink of an eye

Okamgnienie

"Gdyby wrota postrzegania zostały wyczyszczone, wszystko ukazałoby się człowiekowi takie, jakie jest naprawdę — to znaczy nieskończone."

William Blake

Dziś przyszła pora rozprawić się z ciszą pomiędzy słowami. Zainspirowała mnie do tego kolejna lektura Béli Hamvasa Godzina owoców, która jeszcze mocniej zawładnęła moim sercem niż Gaj laurowy. Czytam ją teraz drugi raz — wolniej, z większą uwagą i zachwytem. Jest w niej dużo mistyki, spraw ostatecznych i przemieniających. To taka hamvasowa kropla miodu, o której pisałam w ostatnim poście — a tej kropli wciąż jest mi mało, wciąż chce się jej więcej.

Żeby opowiedzieć o ciszy między słowami, dobrze jest najpierw odnaleźć jakąś ciemną bramę, która intryguje swoją tajemnicą. Bo jest tak, jak pisał William Blake:

"Cisza i głos, głos ciszy mieszkają w krainie cieni."

Pisanie o ciszy między słowami jest więc także pisaniem o cieniu i mroku. To miejsce, w którym słowa nieruchomieją, w którym czas traci znaczenie i w którym może dokonać się doświadczenie przemiany. W takiej ciemnej przestrzeni robi się miejsce na cuda, na światło, na przekroczone "ja".

W tym miejscu słowa stają się zbędne, bo najważniejsze sprawy życia przekraczają możliwości języka. Dokładnie tak, jak pisał Wittgenstein:

"O czym nie można mówić, o tym trzeba milczeć."

Czyż nie zamieramy w milczeniu z zachwytu — albo w obliczu ogromnego cierpienia? Brakuje nam wtedy słów. Nie są już potrzebne, bo cisza rozumie więcej i znosi więcej. Robi miejsce na to, co niepojęte.

Mistrz Eckhart, poszukując tej przestrzeni tajemnicy, szedł jeszcze dalej. Pisał, że aby tam dotrzeć, trzeba opuścić samego siebie. Prosił Boga, by uwolnił go od Boga — bo dla rozumu Bóg jest ciemnością, której nie potrafi rozpoznać, lecz dla duszy jest światłem. W najgłębszym centrum duszy — pisał — człowiek odnajduje coś, co nigdy nie zostało stworzone i nie może zostać zniszczone: iskrę duszy.

Tej cichej, ciemnej przestrzeni nie trzeba się bać. Nie jest pusta — jest żywa. Jest miejscem narodzin, miejscem dotknięcia tajemnicy. Mistrz Eckhart nazwał tę ciszę i ciemność "gruntem duszy". To właśnie tam — jak pisał William Blake — wrota postrzegania zostają wyczyszczone i wszystko ukazuje się takie, jakie naprawdę jest: nieskończone.

I tu wracam do Béli Hamvasa. W rozdziale Melancholia późnych dzieł pisze on o wielkich artystach, którzy u kresu życia zaczynają rozumieć, że nadchodzi czas ciszy. Hamvas notuje:

"Zrezygnować — nawet ze słowa. Zrezygnować, mówi Lao-tsy, oznacza pozostać całym. Być krzywym znaczy stać się prostym. Być pustym znaczy zostać napełnionym."

A wszystko dlatego, że:

"W istnieniu wzmocnionym przez nieustanną bliskość śmierci spalają się wszystkie brudy. Co pozostaje? To, co prawdziwe."

Dlatego — jak zauważa Hamvas — Szekspir w swojej ostatniej sztuce Burza pisze:

"Spocznij tu, moja sztuko."

Artysta już wie, już rozumie, że dalej najpiękniej będzie w ciszy.

Ostatnia melancholia — pisze Hamvas — to miejsce najbardziej intensywne w całym istnieniu, bardziej intensywne nawet niż raj Logosu, raj słowa.

Tak więc między słowami dzieje się mistyka — olśnienie, którego doświadczenie trwa tylko okamgnienie. Bardzo trudno opisać to miejsce językiem. Najbliżej prawdy o nim są artyści — choćby poeci.

Choćby Krystyna Miłobędzka, która pisała w swoich wierszach:

"zanim słowo — jest cisza" i jeszcze "najwięcej dzieje się pomiędzy"

pssst ...

To byl bardzo wymagajacy tekst. Mam nadzieje, ze dotrwaliscie do konca cali I zdrowi. Obiecuje, ze nastepny post bedzie leciutki jak ptasi puch.

Z miloscia,

K

I zapraszam tam ---->

fb: @between.words.2025

in: @kasia_m.baranowska

In the blink of an eye

"If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is — infinite."

William Blake

Today it feels like the right moment to face the silence between words. I was led to it by another reading of Béla Hamvas's The Hour of Fruits, which has taken hold of my heart even more deeply than The Laurel Grove. I am reading it now for the second time — more slowly, with greater attention and wonder. It is filled with mysticism, with ultimate and transforming matters. It is like that Hamvasian drop of honey I wrote about in my last post — and still, one drop is not enough; one longs for more.

To speak about the silence between words, it helps first to find a dark gate — one that draws us in with its mystery. For as William Blake wrote:

"Silence and voice, the voice of silence,

dwell in the shadowy land."

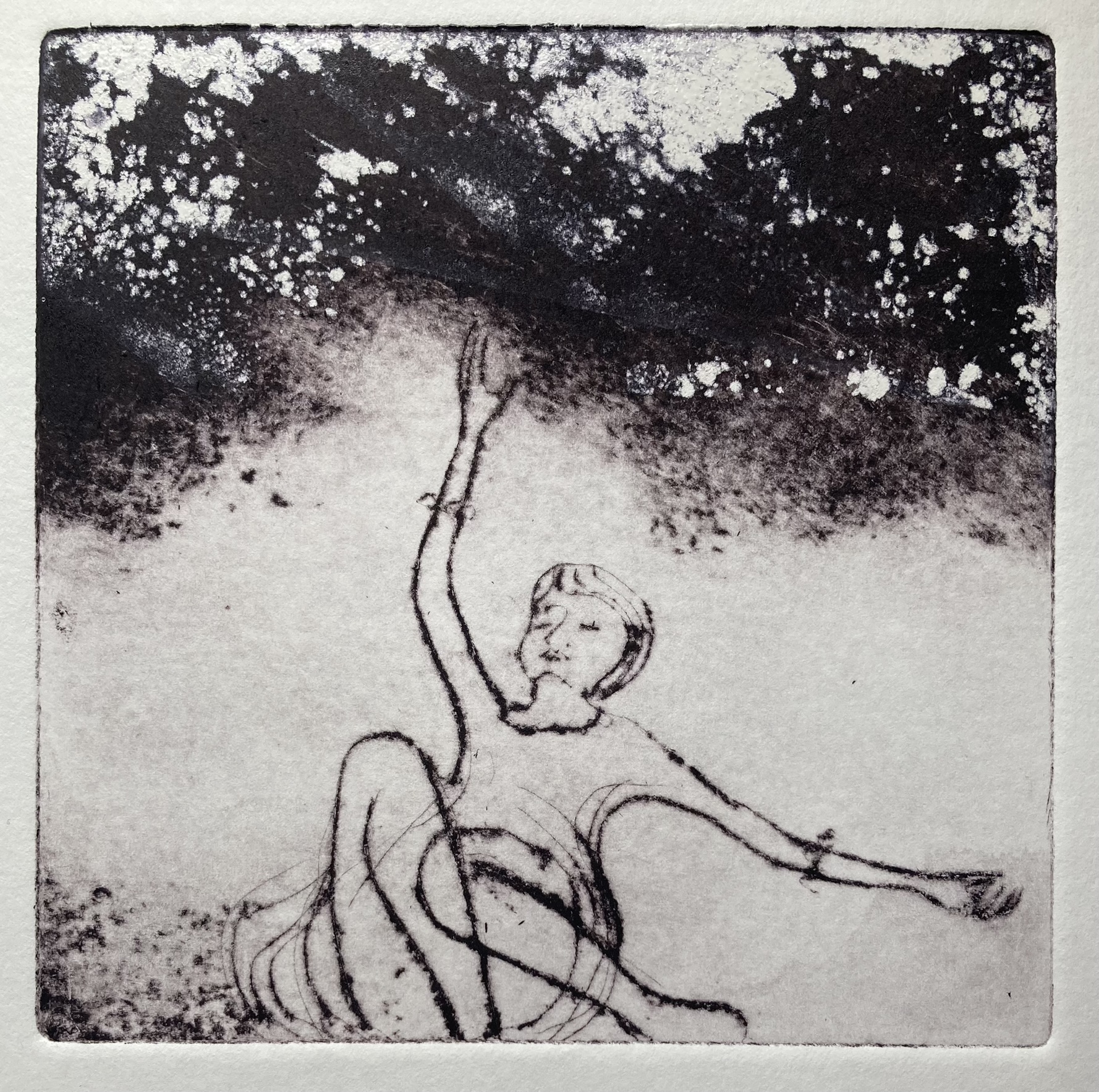

Writing about the silence between words is therefore also writing about shadow and darkness. It is a place where words fall still, where time loses its meaning, where transformation may occur. In such a dark space, room is made for miracles — for light, for the self that has been crossed beyond.

Here, words become unnecessary, because the most important matters of life exceed the limits of language. Exactly as Wittgenstein wrote:

"Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent."

Do we not fall silent in awe — or in the face of immense suffering? At such moments words fail us; they are no longer needed, for silence bears and understands more. It makes room for what cannot be grasped.

Master Eckhart, seeking this space of mystery, went even further. He wrote that to reach it one must leave oneself behind. He prayed that God would free him from God — for to the intellect God is darkness it cannot comprehend, yet to the soul He is light. In the deepest center of the soul, Eckhart wrote, one finds something that was never created and can never be destroyed — the spark of the soul.

There is no need to fear this quiet, dark space. It is not empty — it is alive. It is a place of birth, a place where mystery is touched. Eckhart called this darkness and silence the "ground of the soul." It is there — as Blake wrote — that the doors of perception are cleansed, and everything appears as it truly is: infinite.

And here I return to Béla Hamvas. In the chapter The Melancholy of Late Works, he writes about great artists who, toward the end of their lives, begin to understand that the time for silence is approaching. Hamvas notes:

"To renounce — even the word. To renounce, says Lao-tzu, means to remain whole. To be crooked means to become straight. To be empty means to be filled."

And all this because:

"In an existence strengthened by the constant nearness of death, all impurities are burned away. What remains? That which is true."

Thus, as Hamvas observes, in his final play The Tempest, Shakespeare writes:

"Lie there, my art."

The artist already knows, already understands, that beyond this point the greatest beauty lies in silence.

"The last melancholy," writes Hamvas, "is the most intense place in all existence — more intense even than the paradise of Logos, the paradise of the word."

And so, between words, mysticism unfolds — a flash of illumination experienced only for an instant. The blink of an eye. It is very difficult to describe this place in language. Artists come closest to its truth — poets, for instance.

Such as Krystyna Miłobędzka, who wrote in her poems:

"before the word — silence" and then as well "most happens in between."

psssst....

It was a very demanding text. I hope you made it to the end safe and sound. I promise the next post will be as light as a feather.

With love,

K

You will find me there too ---->

fb: @between.words.2025

in: @kasia_m.baranowska

I will illustrate this image with "Scene with Cranes" by Jean Sibelius.

K.